How a Failed Business Model Birthed the Right One

Lessons in pivoting with purpose and finding strength in strategic failure.

Some people stumble into entrepreneurship.

She was born into it—quite literally.

At just two years old, she was sweeping out sawdust from unfinished homes while her father worked construction jobs. He paid her in cash. She spent it on candy. And just like that, the rhythm was set: build something, earn something, own your effort.

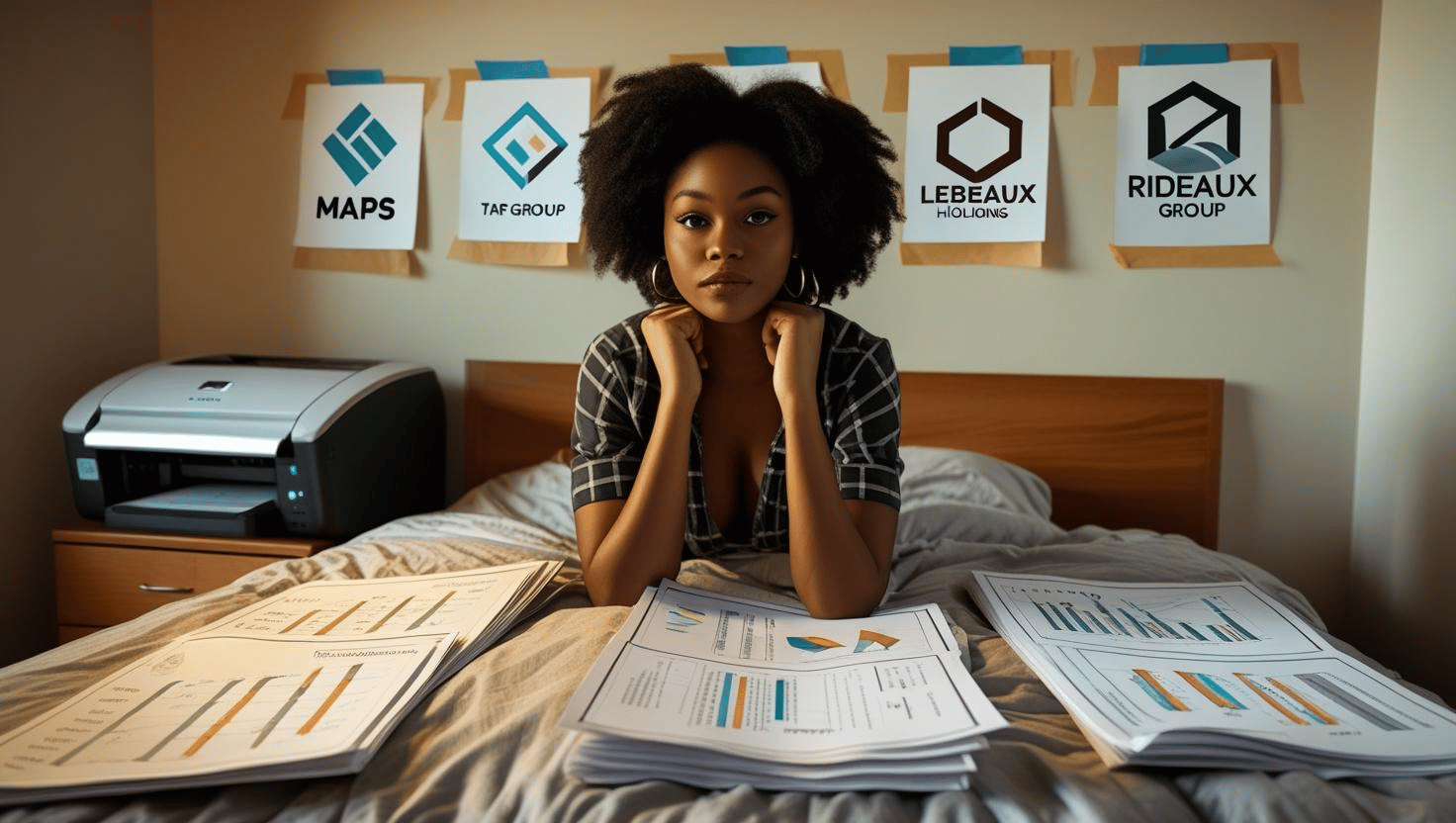

By college, she wasn't dreaming of becoming an entrepreneur—she already was one. Her first business was called MAPS—short for Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations Services. It was a lean operation, built out of dorm rooms and libraries, where she researched and wrote business plans for small organizations and nonprofits who didn't have the budget for traditional firms.

From there, she built company after company:

TAR Group. LeBeaux Holdings. The Rideaux Group.

All full-service. All ambitious. All smart.

But here's the thing no one tells you when you're brilliant, Black, and trying to build something real: strategy alone isn't enough when the world's not set up for your structure to thrive.

Sometimes the business model fails. Not because it's wrong—

but because it no longer belongs to the version of you that outgrew it.

Where it all began - from construction sites to business plans.

The Pattern of Building

She kept building. Each company smarter than the last.

Each pivot closer to the truth.

But there came a point—after losing contracts, funding, and sometimes entire teams—where it became clear:

The old way didn't fit anymore.

The world of agency-first, burnout-later wasn't sustainable.

The climb, the grind, the endless proposals—it all cost more than it returned.

So she did what strong builders do:

She stepped back.

Sat still.

And listened.

Sometimes you have to dig deeper to find what actually works.

The Emergence

Out of that silence came something deeper.

Not just another brand. Not just another service.

A model—rooted in clarity, sovereignty, and technical brilliance.

It didn't need to compete with the old systems because it rewrote them.

Today, she builds under the banner of Ink, with active ventures like:

- COOai, an AI-powered assistant for small businesses

- Bougie & Green, an eco-lifestyle brand with global reach

- Molly Rusty, a storytelling platform reclaiming cultural legacy

And all of it is scaffolded by what didn't work—by models that stretched too thin, moved too fast, or tried to prove instead of embody.

Strategic Failure as Foundation

The consulting business wasn't a failure in conventional terms. It generated revenue, satisfied customers, and demonstrated market demand. But it was a strategic failure because it didn't align with her actual goals and priorities.

That kind of failure is valuable precisely because it forces deeper questions about what success actually means. It creates space to examine assumptions about business models, growth strategies, and the relationship between work and life.

Most importantly, strategic failure teaches you to pay attention to alignment rather than just optimization. To ask not just "Does this work?" but "Does this work for me, in the context of the life I'm actually trying to build?"

The Right Problems, The Right Model

What she learned is that she'd been solving the right problems with the wrong business model. The insights about operations, strategy, and systems that made her effective as a consultant were still valuable. But their highest expression wasn't in custom solutions for individual businesses—it was in standardized products that could help many people solve similar challenges.

The Yenaffit holding company model emerged from understanding that she didn't want to build one perfect business. She wanted to build multiple complementary ventures that could support each other while serving different aspects of her interests and expertise.

This approach allows for portfolio risk management—if one venture struggles, others can compensate. It creates opportunities for cross-promotion and shared resources. Most importantly, it honors the reality that complex people have complex interests that can't always be contained within a single business focus.

Learning from What Didn't Work

The failed consulting business taught her that conventional wisdom about entrepreneurship doesn't always apply to specific circumstances. That market validation doesn't guarantee personal satisfaction. That you can execute a business plan perfectly and still end up in the wrong place.

More importantly, it taught her to pay attention to what works rather than what should work. To design around actual constraints rather than theoretical ones. To prioritize alignment over optimization when the two come into conflict.

The businesses that emerged from that failure are more sustainable, more interesting, and more aligned with how she actually wants to live and work. They're built on the foundation of understanding what doesn't work, which turns out to be more valuable than starting with assumptions about what should work.

The Truth About Failure

Failure didn't end the vision.

It shaped it.

And what emerged was the right model—not because it was perfect, but because it was finally honest.

Sometimes the right business model can only be discovered by first building the wrong one and learning from its limitations. The failure becomes fertilizer for something better—if you're willing to ask the uncomfortable questions and act on the uncomfortable answers.

Each failed model teaches something essential about alignment, sustainability, and the difference between what looks successful and what actually serves the life you're trying to build. The key is listening to what the failure is trying to tell you, rather than just trying to fix the obvious problems.

Because sometimes the problem isn't execution. Sometimes the problem is that you're executing the wrong thing entirely. And recognizing that difference—that's where the real breakthrough happens.